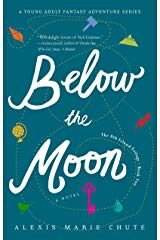

Below

the

Moon

Book Two in The 8th Island Trilogy

By Alexis Marie Chute

An epic fantasy adventure series called The 8th Island Trilogy. Above the Star, book one, was released in 2018, featuring multigenerational and diverse characters. Books two and three—Below the Moon will hit bookshelves in OCT 2019 and Inside the Sun— and 2020 .

Ella Wellsley is not your typical teenager. Cancer left her mute, but not powerless. Trapped in a parallel dimension, Ella rallies her strength to join her family—her mother, Tessa, her grandpa Archie, and her magical boyfriend—in locating the cure to her illness. This cure is entangled in the fate of all worlds, and threatened by the presence of an evil Star anchored in the sea. The Star has thrown life everywhere into chaos—and it is Ella who holds the key to unlocking its mystery.

Caught in a web of betrayal, mistaken identities, secrets, and love triangles, Ella, Tessa, and Archie must overcome their troubled pasts to ensure a future for all worlds. On this journey—armed with unearthly abilities and unexpected allies—each member of the Wellsley family will learn the power of love in the face of their greatest fears

Today we bring you Chapter One

ELLA

Lightning illuminates the sparse room where Luggie and I stand in silence and makes all the glass buildings visible. For a moment, I can see everyone in the city. Olearons prepare the wryst drink and vulai bread in the great kitchen for our imminent journey to the Star. Inside a molded

glass nursery, a red-skinned mother rocks her frightened baby. The Lord of Olearon struts around in his fanciest garb, overseeing everything but doing nothing. In contrast, Grandpa Archie and Dad dash here and there helping everyone. Olearons and humans sit at long glass tables, eating the tiny harvest, while others struggle to sleep. Then I see Mom and Captain Nate. Ugh. Their flirting is disgusting. I can’t stomach the sight of them, so I look up.

glass nursery, a red-skinned mother rocks her frightened baby. The Lord of Olearon struts around in his fanciest garb, overseeing everything but doing nothing. In contrast, Grandpa Archie and Dad dash here and there helping everyone. Olearons and humans sit at long glass tables, eating the tiny harvest, while others struggle to sleep. Then I see Mom and Captain Nate. Ugh. Their flirting is disgusting. I can’t stomach the sight of them, so I look up.

The dark sky is lit with splashes of purple, yellow, and blue as the pronged fork of

electricity lacerates the atmosphere, shattering it as if it were pottery. Through the grassy

pathways between the geometric buildings, past the warrior-training paddocks, and beyond to the western pasture, I can make out more tall slim red bodies going about their normal lives—though nothing is normal. Not for me in this new world, not for the Olearons, not for any race on the island of Jarr-Wya.

Luggie’s yellow eyes squint at me, distrustful. He shoves a tunic into a sack. Both were

given to him by the Olearons, and he accepted them begrudgingly. The tunic is for protection

from the erratic weather on Jarr-Wya. He needs it. We all do. The sun is pale like an unripepeach. It looks ill in the sky and gives little warmth. It’s easy to relate to its feeble quality. I

wonder if I’m fading away like the sun and exactly how much fight I have left in me. Luggie’s sack is to carry his belongings on our journey to Baluurwa the Doomful, where our new company hopes to find a tunnel to the hiding place of the Star. Not all of us will set out on this mission. Not the dead ones: Olen, the Maiden of Olearon, Eek, or Valarie, the cruise director, twice-killed. Luggie’s sister Nanjee wasn’t the only casualty. Luggie is painfully stubborn, just like me—though I’d never admit that to Mom. He is

almost six thousand sunsets old, which if my math is right makes him sixteen in human years.

He’s still learning to wield the Bangols’ control over the earth, rock, and clay. His head-stones

have grown in, but they’re not like the ones that break through the skin of the adult Bangols

above their cheekbones. He’s immature, which is obvious from his stubbornness alone.

Luggie is mad at me. He hasn’t spoken a word since we were rescued by Kameelo out of

the eastern sea and flown to the glass city of the Olearons. True, I had to punch Luggie in the

face to knock him out. If I hadn’t, he’d have continued to resist Kameelo and might have

drowned all three of us.

I smile weakly in Luggie’s direction—a white flag of peace—but this only further sours

his mood.

Rain begins to patter against the glass. Great. Yes, I’m being sarcastic. The only thing

my cancer hates more than physical exertion is physical exertion through mud. The one solace I

have is that right about now I’m missing my grade nine social studies exam on technology

through the ages. I intended to study for this on the Constellations Cruise Line ship, the Atlantic

Odyssey, but then Grandpa Archie used a portal jumper, or Tillastrion, and accidentally

transported our whole ship to Jarr. Besides causing the exhaustion, my cancer has stolen my ability to speak. It’s been

months. The no-talking thing hasn’t truly bothered me until now, when I have something important to say.

“What do I have? What here is my own?” Luggie says, fuming, finally speaking to me as he stares at the sack that hangs in his hands like a deflated balloon. The tunic the Olearons gave him is a brilliant blue like their warriors’ jumpsuits. “How can I wear it, Ella? The color alone makes me want to wretch. I have loathed the Olearons right from when I was birthed from stone.

And it is justified, I might add. Stop shaking your head at me, Ella—I have learned what humans

mean when they turn their heads like that.” I can’t yell at him to tell him to grow up. To stop whining. Maybe it’s a good thing I’m

unable to communicate except through my drawings. I care about Luggie, but there are many things I want to say in the heat of this moment that I might regret. I too stubbornly believe I’m right.

“One day I will shred this garment, or bury it, or use one of ten other ways to dispose of

something so putrid.” I can’t help but roll my eyes at him. Luggie continues to mumble under his breath, now in

the Bangols’ sharp dialect, as he concocts more ideas of how to destroy the tunic at his first

opportunity. Tentatively, I take the three steps across Luggie’s small room in the Olearons’ glass

city. I touch his arm, but he wrenches it away.

“I have packed it not because I forgive them, or you, but just in case,” he says, relenting. He nudges his shoulder against the glass wall that is cut so precisely that its molded, magic curves are barely discernible. The wave of cloudy glass shimmers and turns transparent at his touch. He’s learned how his place of refuge among the Olearons functions, and he now watches

the red creatures through the translucent shimmer as they hustle to and fro in the rain, donning the overgrown leaves of the blue forest like storm slickers. “How can I trust you after your blow to my face and Kameelo putting his hot hands on

me, stealing me from the eastern shore? You two stopped me from mourning my fallen Bangol soldiers, friends, and family. From mourning Nanjee.” Luggie nearly chokes. I can tell he feels a pang of sadness at his sister’s name. He shuts his eyes, dulling their lemon light to a faint glow that radiates through his eyelids. Nanjee is my only regret. I’ve never had a sibling, so it’s hard for me to understand how Luggie feels, though I have lost someone I love. Grandma Suzie. I know that grief is like being

cut in two. My annoyance toward Luggie wanes. Yes, I saved his life by punching him, but in doing so I delivered him into the care of his enemy. I’d be mad too. And heartbroken. I think back to when Grandma Suzie died—that was my first experience with death, and I don’t think I’ve become much better at dealing with it since. One moment, Grandma Suzie occupied space in the world. There was an energy around her that caused anyone nearby to light up, to smile. I remember running from room to room in

our Seattle bungalow, searching for that feeling, for Grandma. The only thing I discovered was

weak traces of her on her clothing and her books, in her stained teapot decorated with painted

strawberries and their curling vines, and on the breeze when I ran her daily walking path. For a

while, the ruts from her walker etched that path like handwriting, but they grew shallower,

fainter, like my memory. In the spring, they were still there, frozen in time. Now I continue to

imagine her smile and creased cheeks when I close my eyes.

I suspect no one ever becomes better at grief. It’s not like practice makes it easier.

Humans—I can’t speak for the Bangols or Olearons—must learn to hide its pang stealthily. I did

my best to comfort Grandpa Archie, but I was too young. All I understood about grief was the

confusion of absence without explanation. I brought Grandpa my favorite toys. Rolled myself

into a ball on his lap, his heart beating against my cheek so it wasn’t terribly lonely in his chest.

Grandpa Archie had me and Mom—and Dad too, until he disappeared—to lean on. Luggie must

feel all alone.

“My first desire is to weep,” Luggie admits, as if reading my face and wandering

thoughts. I’m startled briefly, taken away from missing Grandma to being back in Luggie’s glass

room with the grass carpet. Back to being with this Bangol who peers over his shoulder to where

I stand awkwardly.

He goes on. “But my second desire is to avenge. If Kameelo had not robbed me of my

right to mourn, then I would have climbed from the sea, up the stone pillar that supported the

cells above it. I would have collected what was left of Nanjee’s body and given her the ritual

burial that is the Bangols’ way, not the scorching ceremony of the Olearons. We Bangols are

from the earth. Our bones are made of clay. Our blood flows with the water of the deep. Our eyes

are shards of sunshine, scattered in tiny quantities, sunbeams planted in the earth. Can you even

understand this, Ella? I am speaking in your tongue, but can you understand?”

My head bobbles quickly in a nod that is both an effort and an apology. I lift my hand to

touch his smooth grey skin, but he shuffles beyond my reach. Luggie smashes the sack onto the

grass. He exposes his teeth and I don’t mean to, but I stumble back, afraid.

Luggie says, raging, “The sunlight grows into our beaming eyes, giving vision to our

young, touching us with light. The Bangols come from the foundation of Jarr, from the very land

of Jarr-Wya. It is only right that Nanjee, the princess of the Bangols, be returned to the place

from where she was birthed. Those Olearons, they knew. Taking me away from the east . . . I

will get back there. Maybe all that will remain is bones, but I know Nanjee’s head-stones. I will

find her. I will honor her life, my beautiful, brilliant sister.”

Luggie lifts a hand to the glass wall and scratches five straight lines with his sharp nails.

He steps away so the distortion returns, shielding him and me from the activities of the city. The

opaque reflectiveness is a dull mirror, though it vibrates at the deep-cut lines.

Luggie’s muscles are tight, rippling through him to his clenched fists. I’m sure his nails

puncture his palms. He grinds his dagger-fine teeth and growls. “And Ella”—Luggie whispers

now—“Ella, why them? Why did you choose them over me?”

He kicks the sack. It bounces against the glass door, which shimmers, and for a moment

the mirror returns to glossy translucency, allowing Luggie and me to catch a glimpse of Duggie

Sky running by. The boy pauses, then steps back as he notices us. The four-year-old rushes to the

door and presses his nose into a pancake against it. I can’t help but laugh, which comes out

horribly. Cancer has corrupted even my laugh, trapping me in a silent world, though it’s loud in

my head, the place where I collect all the things I wish to say.

Duggie-Sky has a square of the Olearons’ vulai bread in one hand and a mud ball in the

other. His face still presses against the glass as he raps on the door with his elbow. Luggie

swings it open.

“Hi!” says Duggie-Sky cheerfully. His dark brown skin glows with raindrops, and his

boyish round cheeks are flushed from evading the young Olearon tasked with minding him until

the company departs. Since the transformation gifted to him by Rolace the man-spider in his

web, not only is Duggie-Sky as fast as a blink, but he’s also grown smarter. Perceptive.

“You sad, Luggie?” Duggie-Sky asks. “Wanna play catch?” The boy moves with the

agility of a basketball player. His eyes tell me he understands what’s going on around here—

probably better than I do—though his voice hasn’t lost the childlike slur.

Hi, I say in my head and wave at the boy who stands two feet shorter than me. Duggie

Sky beams and takes a bite of vulai bread. His tight black curls bounce as he chews. Luggie

doesn’t turn, so I smile and raise my hands. He tosses me the ball, a perfect sphere of mud just

like the ones the conniving Bangol, Zeno, taught him to make.

“Snack?” Duggie-Sky asks, holding the bread toward me first, then Luggie. I shake my

head and toss the ball back with terrible aim. Without pausing in his chewing, Duggie-Sky zips

to successfully catch the mud in his free hand. He laughs and vulai breadcrumbs fall out of his

mouth.

“Ugh, I cannot stomach more vulai.” Luggie grimaces.

Duggie-Sky darts around Luggie and peeks at me for a second before disappearing

behind the narrow glass wardrobe. The gift of teleportation, imbued with the magic life force of

Naiu, is well used, and daily. Duggie-Sky even exercises it in pestering Grandpa Archie, who is

always a good sport and even does much of the initiating on his own.

I jump behind Luggie. As I peek around his stocky body, Duggie-Sky leans out of his

hiding place, then vanishes again. Suddenly, I feel a tap, tap, tap on my back. I jump and turn at

the same moment and thrust my hands forward to tickle the boy’s belly. He giggles, scrunching

his neck, and tumbles down onto the grass floor of the chamber, pulling me down by the wrists. I

can’t help but laugh. “Aweeak!” I sound horrible and am suddenly self-conscious. Luggie

catches my gaze.

“Be careful, child,” he says. “She is not well.”

My weakness, the nausea and frailty from the tumor, are my business, and I would say as

much if I could even whisper the words. The way Duggie-Sky looks at me now, less like a

playmate than a fragile decoration on a mantel, to be appreciated from afar, and certainly not

touched . . . ugh, I hate that look. I remember that expression on the faces of my classmates at

school. It’s true—physically I couldn’t keep up with them, but I was still me.

Luggie turns away from Duggie-Sky and me, and the unbalanced feeling fills the modest

space. To tip the energy toward peace, I sweep my hands outward, one to the left and one to the

right, as if brushing away crumbs after a meal. The gesture is American Sign Language, meaning

finished. Duggie-Sky gets the idea and leaps to his feet.

“They’re almost ready out there,” he says happily, and on his way out adds, “’Kay, bye!”

Duggie-Sky disappears with a swoosh through the entryway.

“Why does he bother with doors?” Luggie mumbles.

Before the door clicks shut behind the gleeful child, I catch the edge of it and take a step

out. It’s clear that I’m wasting my time here; I’m sure I can help with packing in the octagon

paddock, if they’ll let me. My eyes find Luggie’s and I shrug, wave goodbye, and step out into

the damp, windswept pathway.

“Wait,” he says.

I want to scream. Instead, I close my eyes at the whipping of the breeze. It animates my

long blond hair, dancing it around my face like a puppet’s strings. The wind has been erratic.

Strong like a bull. Wild like a snake. It’s one effect of the Star’s poisoning of the island, making

the Bangols—their king Tuggeron, also known as Tuggs—hungry to expand the Bangols’

territory. The Star is also to blame for creating the Millia sands, which leeched the blood from

half the Constellations Cruise Line passengers. People I sat beside at the ship’s mammoth tables

in the dining hall and swam with in the bean-shaped pool on the deck. I can’t help but shudder.

The Star must be stopped.

“Your laugh . . .” Luggie begins. “It is jarring, a pained screech. I do not understand how

the illness at your neck saddens you, how it makes you weak, but still the sounds you make are

beautiful to me. Even in my anger, Ella Wellsley, I need to protect your laugh.”

My hand is on the scrolling glass handle. I’m unable to walk away, to leave Luggie alone

with his sack and the despised blue tunic. I’m also stubbornly unwilling to return to his chamber.

Again, I find my blue eyes locked with Luggie’s vibrant yellows. He’s the first to look away. I

can’t hold back the tears.

I give in.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

https://www.facebook.com/AlexisMarieProductionsInc/

https://twitter.com/_Alexis_Marie

https://www.youtube.com/user/AlexisMarieChute

https://www.instagram.com/alexismariechute/

Visits: 14